Daughter of Liberty finaled in the prestigious American Legacy Book Awards last spring! I neglected to post the news on the blog, so here it is!

The American Patriot Series

Friday, October 11, 2024

Friday, April 26, 2024

I have a new interview up on Christine L. Henderson's blog Reading and Writing Books! We had a fun conversaation. Check it out and leave a comment!

You'll see that she picked up the old, out of print edition of Native Son, still carried by some resellers on Amazon, but thankfully the new edition is easily found.

Saturday, May 27, 2023

Wednesday, April 5, 2023

Weather that Affected the Revolution: A Storm Ends the Siege of Boston, 1776

|

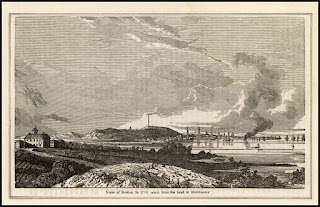

| View of Boston in 1776 from Road to Dorchester |

Following the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, American militias besieged Boston, which was occupied by the British Army under the command of General William Howe. General George Washington took command in July of what then became the American Army. The two armies remained in a stalemate through the summer, fall, and winter.

| Colonel Knox Bringing the Cannons from Fort Ticonderoga |

In January 1776, Colonel Henry Knox reached the American camp with heavy siege guns and gunpowder that had been dragged on sleds across the snow all the way from captured Fort Ticonderoga. There was still not enough gunpowder to sustain a bombardment long enough to drive the well-entrenched British out of the city, however. And with the ground frozen at least a foot deep, it would take more than one night to dig fortifications atop a steep bluff that overlooked Boston and its harbor, which was occupied by the British Navy. If they were seen by the enemy, work crews were sure to draw heavy fire.

A brilliant solution was proposed: Place pre-made wooden frames on top of the ground, stuff them with hay, and cover them with dirt to construct parapets. Plans proceeded apace, and on March 2 the Americans began a bombardment from several points around Boston as a diversion. The British responded in kind, and the same took place the following night. Then at dusk on the 4th, with mild temperatures and under a clear sky and full moon, the Americans’ heaviest bombardment crashed into the town while 3,000 men worked feverishly to fortify two of the steep hills known as Dorchester Heights. That night they built the embankments, installed at least 20 pieces of artillery, cut down trees to make abatis and to provide a clear line of fire, and manned the fortification with a large number of well-armed soldiers.

That afternoon transports lined up in the harbor off Castle William facing Dorchester Heights. Aboard were the troops ordered to storm the American fortifications the following morning. In the evening, as rain began to move into the area, Washington reviewed the American defenses on the heights.

He had no sooner returned to headquarters than a violent storm suddenly raged into the area. All night brilliant flashes of lightning and the rolling boom of thunder shook Boston and its environs. A heavy gale blew torrents of rain and snow horizontally, tearing limbs from trees, wreaking destruction on land and sea, and terrifying residents. Its fury did not abate until the inky sky finally began to lighten toward a sullen dawn.

|

| Washington Enters Boston |

Howe immediately began preparations to evacuate his army. On March 17, the heavily laden British ships slipped down the harbor toward the sea. The following day Washington took possession of Boston, formally ending the siege eleven months after it began.

Wednesday, October 19, 2022

New England's Dark Day

|

| Dark Day mural, painted by Works Progress Administration artist Delos Palmer in Stamford, Conn., Old Town Hall. |

In Forge of Freedom Carleton relates an account he heard of a strange, unsettling early darkness that had descended over the New England states a few weeks earlier. This is, in fact, a real historical event that occurred on May 19, 1780.

The weather had been cool in the north for most of the preceding month. Although the sky remained clear, a dirty yellow tinge colored it, and for several hours after sunrise and before sunset the sun held a reddish cast. But what happened that Friday morning was completely unexpected.

The morning began mostly cloudy, and shortly after 9 o’clock “came on an appearance over the whole visible heavens a light grassy hue nearly the color of pale cyder,” according to one contemporary diary entry. Around noon a darkness descended that was so deep the birds sang their evening songs, then fell silent and retreated to their nests. Frogs began to peep. Chickens returned to their roosts and cows to their stalls. In some areas an almost impenetrable darkness made travel difficult, if not impossible.

|

| Image from Our First Century, 1776-1876, Richard Miller Devens (1880) |

“It was so terrible dark that we could not see our hand before us,” one diary entry reads. A letter sent from Exeter, NH, records that “the inky black was probably as gross as ever has been observed since the almighty first gave birth to light….A sheet of white paper held within a few inches of the eyes was equally invisible with the blackest velvet.” A professor at Cambridge, MA, observed that “In some places the darkness was so great, that persons could not see to read common print in the open air….The extent of this darkness was very remarkable.”

A minister at Westborough, MA, wrote, “By 12, I could not read anywhere in the house—we were forced to dine by candle light. It was awful and surprising.” A professor in New Haven, Connecticut, reported, “the greatest darkness at least equal to what was commonly called candle-lighting in the evening. The appearance was indeed uncommon, and the cause unknown.” He also noted that low clouds took on “a strange yellowish and sometimes reddish appearance…an unusual yellowness in the atmosphere made clean silver nearly resemble the colour of brass.” Others remarked the effect on the colors of grass and foliage: “An uncommonly lovely verdure, a deepest green, verging on blue” and “so enchanting a verdure as could not escape notice, even amidst the unusual gloom that surrounded the spectator.”

The eerie darkness extended north to Portland, Maine, and west into the Hudson Valley. It was noticeable as far south as New York City and northern New Jersey, where General George Washington noted it in his diary while camped at Morristown. It didn’t extend to Philadelphia but seemed to center around northeastern Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire, southwestern Maine, and coastal areas bordering the region.

The unprecedented, unexplained darkness caused considerable consternation and even terror, as you can imagine. Many people feared God’s anger or demons to be the cause. It was variously reported that “persons in the streets became melancholy and fear seized all”, and the darkness “caused great terror in the minds of abundance of people”. Members of the Connecticut Legislature believed the Day of Judgment was at hand and adjourned for the day. Weeping crowds thronged into churches to pray.

|

| View of Boston Harbor |

At the time there were no certain means to determine what caused this strange event, which lasted only for one day. There were clues, however. Rain fell that day across several areas, and at Ipswich, MA, rainwater collected in tubs was covered by black scum like ashes and had a strong sooty smell. The air in Boston smelled like a “malt-house or coal-kiln”. Noting that the water was thick, dark, and sooty, appearing like the black ash of burned leaves, but “without any sulphureous or other mixtures,” Professor Samuel Williams of Cambridge, MA, theorized that the darkness was due to the atmosphere being highly charged with vapors.

Williams was essentially correct, though he had no way to definitively prove it. The mystery reigned for many years before finally being solved in 2007. That year a team led by Richard Guyette, a forestry professor at the University of Missouri, used a dating technique called dendrochronology to determine that in the spring of 1780 a huge fire swept across a large area north of Ontario, today Algonquin Provincial Park. It’s now known how smoke from large fires interacts with the atmosphere and wind patterns, and Guyette concluded that this was the likely cause of New England’s strange dark day.