I understand that negative reviews are to be expected in the business I’m in. All artists understand that. Not that we especially like it, of course. After all, who likes being told by others that you did a poor job at something you poured your heart and soul into? But I accept that not everyone is going to love my books. Some are going to hate them. That’s par for the course, and it’s a huge comfort to know that many readers love the books I write.

But have you ever gotten a review or a criticism that just plain puzzled you? I’ve gotten a couple recently that have me scratching my head. Following is the first, which is actually a wonderful 5-star review titled: Amazing book by a great author.

“This is an amazing book about the Revolutionary War. It has spies, romance, exciting battles, and interesting historical facts. Be forewarned that this is a continuing seven book series. I have read the first 4 books and now have to wait over a year until the 5th book is published. The reader is left dangling with the heroine in a very perilous situation in the fourth book. This is very disappointing and had I known I might not have started this series.”

I greatly appreciate the very kind, positive comments about the series in the first couple of sentences! It’s wonderful feedback like this that keeps me writing on days when I feel like it’s all worthless. What has me puzzled is the rest. It makes me wonder whether readers have any concept of how expensive it is to publish a book and especially a series. The worst part is that the reviewer is essentially telling readers not to read the series until all the books are published. If all readers did that, publishers wouldn’t publish any series at all, and the American Patriot Series wouldn’t exist.

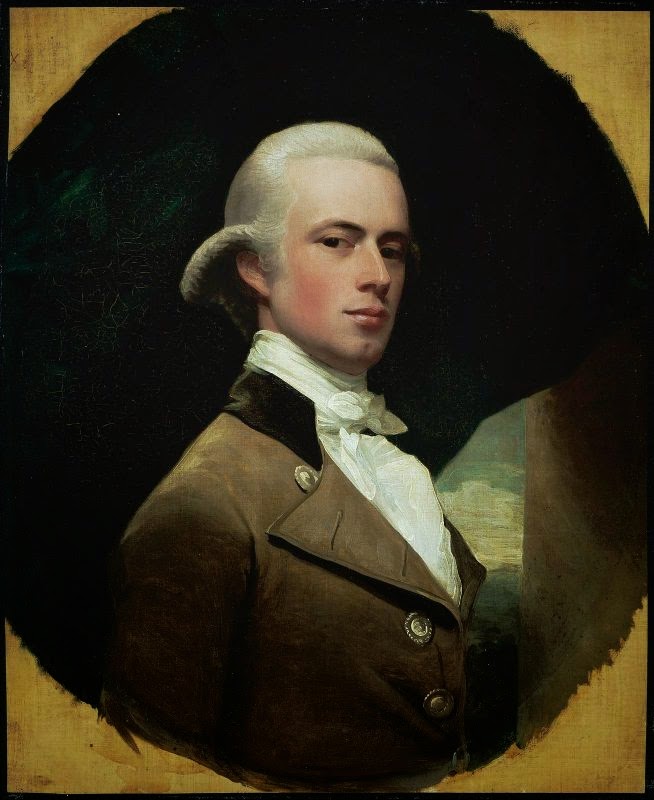

I hope most readers understand that it’s sales that keep series going. If book 1 doesn’t sell enough copies to be profitable, no further volumes will see the light of day. That’s the reason Zondervan and I parted company years ago. Daughter of Liberty and Native Son didn’t get high enough sales figures for them to invest any more money in the series. If I hadn’t believed in it so strongly and felt the Lord’s direct leading to found a small press to publish it and the books of a few other authors in the same boat (and been blessed with the means to fund that endeavor), the American Patriot Series would have ended with book 2. How many series that readers would have loved have completely disappeared because their authors couldn’t afford to do the same?

In addition, ending each volume on a cliffhanger is actually necessary if subsequent books in the series are going to sell. If everything is tied up in a neat package at the end of each volume, what would cause readers to eagerly anticipate the next installment of the story? (The exception is series that feature a different hero/heroine in each book.) Authors have to build suspense at the end of each book or readers are going to forget about the series by the time the next volume comes out. I certainly would—in fact, I have stopped reading series I initially liked for that very reason. I just forgot about it or wasn’t motivated to continue. It’s like Christmas Day. The anticipation that builds up over the year is what makes finally opening all those beautifully wrapped presents under the tree so exciting.

Another issue the reviewer alludes to is the length of time between books. I apologize for that, but I’m by nature a careful and methodical writer. And as anyone who writes fiction, particularly historicals, knows, it takes considerable time to write a story that’s not only entertaining and inspiring, but also historically accurate. With all the research necessary to dig out the historical facts and develop a plot that puts my characters believably into the midst of the real action where they interact with the actual people of the day, not to mention creating deeply conceived, realistic characters in the first place . . . well, there’s simply no shortcut to accomplishing that. And for me it’s not worth writing anything less.

The second review puzzles me even more. It’s generally negative, and it really has me pondering. I need feedback on whether it’s correct about how I handle spiritual issues—what the reviewer calls the “overly drippy religious aspect”—and what the “real” story of my series is. If this reviewer is right on those points, then I clearly need to change things. Or quit. I’ll share that one in my next post.

In the meantime, what are your thoughts about series and cliffhangers? Have you ever been criticized in a way that genuinely stumped you? Did you change anything as a result, or did you believe in what you were doing and how you were doing it and continue?

.jpg)