Saturday, May 27, 2023

Wednesday, April 5, 2023

Weather that Affected the Revolution: A Storm Ends the Siege of Boston, 1776

|

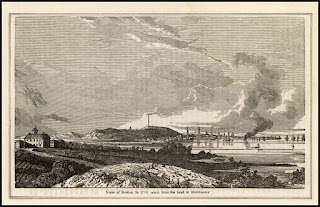

| View of Boston in 1776 from Road to Dorchester |

Following the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, American militias besieged Boston, which was occupied by the British Army under the command of General William Howe. General George Washington took command in July of what then became the American Army. The two armies remained in a stalemate through the summer, fall, and winter.

| Colonel Knox Bringing the Cannons from Fort Ticonderoga |

In January 1776, Colonel Henry Knox reached the American camp with heavy siege guns and gunpowder that had been dragged on sleds across the snow all the way from captured Fort Ticonderoga. There was still not enough gunpowder to sustain a bombardment long enough to drive the well-entrenched British out of the city, however. And with the ground frozen at least a foot deep, it would take more than one night to dig fortifications atop a steep bluff that overlooked Boston and its harbor, which was occupied by the British Navy. If they were seen by the enemy, work crews were sure to draw heavy fire.

A brilliant solution was proposed: Place pre-made wooden frames on top of the ground, stuff them with hay, and cover them with dirt to construct parapets. Plans proceeded apace, and on March 2 the Americans began a bombardment from several points around Boston as a diversion. The British responded in kind, and the same took place the following night. Then at dusk on the 4th, with mild temperatures and under a clear sky and full moon, the Americans’ heaviest bombardment crashed into the town while 3,000 men worked feverishly to fortify two of the steep hills known as Dorchester Heights. That night they built the embankments, installed at least 20 pieces of artillery, cut down trees to make abatis and to provide a clear line of fire, and manned the fortification with a large number of well-armed soldiers.

That afternoon transports lined up in the harbor off Castle William facing Dorchester Heights. Aboard were the troops ordered to storm the American fortifications the following morning. In the evening, as rain began to move into the area, Washington reviewed the American defenses on the heights.

He had no sooner returned to headquarters than a violent storm suddenly raged into the area. All night brilliant flashes of lightning and the rolling boom of thunder shook Boston and its environs. A heavy gale blew torrents of rain and snow horizontally, tearing limbs from trees, wreaking destruction on land and sea, and terrifying residents. Its fury did not abate until the inky sky finally began to lighten toward a sullen dawn.

|

| Washington Enters Boston |

Howe immediately began preparations to evacuate his army. On March 17, the heavily laden British ships slipped down the harbor toward the sea. The following day Washington took possession of Boston, formally ending the siege eleven months after it began.